East Timor & the Politics of Oil

Perth, Australia

Contents

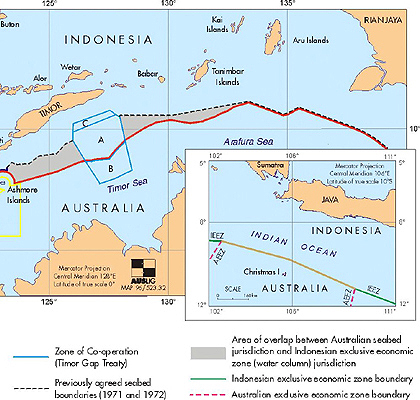

The Timor Gap is the offshore area of the Timor Sea between the eastern end of the island of Timor and Australian waters. The region's Bonaparte and Browse Basins are believed to contain natural gas reserves totaling nearly 40 trillion cubic feet, rivaling the gas reserves of Western Australia's Northwest Shelf (Carnarvon Basin).

In 1971, Australia and Indonesia signed a treaty settling the seabed boundary in the Arafura Sea (east of Timor/north of Australia). In 1972, a second treaty was signed settling the seabed boundary in the Timor Sea (between Timor and Australia). This treaty left a gap, however, in the delimitation of the seabed boundary in the offshore area adjacent to East Timor, now known as the Timor Gap.

Before 1975, Portugal administered East Timor, and Australia was unable to negotiate a seabed boundary agreement with Portugal for the Timor Gap. Since 1975, Australia has supported the 1975 Indonesian annexation of East Timor. In 1978, Australia became the only country in the world to formally recognize Indonesian sovereignty, in return for a share of the spoils, the oil and gas reserves within the Timor Gap exploration zone.

Negotiations between Australia and Indonesia over the ensuing years argued whether they shared the continental shelf, whether the borderline should be equidistant between their coastlines, and whether Indonesia's claim under the international Exclusive Economic Zone concept, with seabed rights extending out to two hundred nautical miles, applied.

Faced with the difficulty of reconciling the two countries' competing claims, the Timor Gap Treaty was signed, and the associated Zone of Cooperation (ZOC) established in 1991, a move condemned by both Portugal (which had earlier relinquished East Timor as a former colony) and the East Timorese, who were fighting for their independence.

The Zone of Cooperation covers 62,000 square km of the Timor Sea, northwest of Darwin (Northern Territory of Australia) and south of East Timor. Its subdivision into three areas; ZOC A, B, and C, has allowed the exploration and exploitation of petroleum to proceed under a comprehensive range of joint arrangements. Indonesia and Australia have jointly administered ZOC area A (ZOCA), with taxes split 50:50, after the producing companies have recovered their costs. The southern (B) and northern (C) areas are individually under the control of the nearest country, with each government receiving 10% of all taxes from production in the others' zone.

ZOC, Money for East Timor? (back to top)

Australian Labor party foreign affairs spokesman Laurie Brereton said he estimated that an East Timorese administration would have access to $A150 million a year in oil and gas royalties, this when BHP commenced oil production at its Elang, Kakatua and Kakatua North Fields (Zone A) in 1998. Royalty revenues at present are only around $2.5 million a year to each government, but the figure should rise considerably when BHP begins operating the Bayu-Udan natural gas project (if it goes ahead) as planned in 2002. By one estimate, the oil and gas reserves in the treaty zone are worth $19 billion over the estimated 20-year life of the projects.

Although Australian officials admit that an independent East Timor would not be obliged to continue with the agreement (which East Timor was excluded from playing any part in), indications are that independence leaders will honor the terms of the treaty, primarily because it will provide a valuable source of revenue.

Prior to the recent referendum in East Timor, the National Council of Timorese Resistance (CNRT), formed by the main East Timorese political parties, issued a statement urging international oil companies to recognize that their interests would be best served by supporting calls for Timorese self-determination, seeking a mutually beneficial deal with the Timorese leadership. This, it said, would "enable oil companies to operate in a secure and predictable environment, for the benefit of all stakeholders…. the Timor Gap contractors commercial interests will not be adversely affected by East Timorese self-determination. The CNRT supports the rights of the existing Timor Gap contractors and those of the Australian government to jointly develop East Timor's offshore oil reserves in co-operation with the people of East Timor."

To date, there has been expenditure of over US$700 million in Area A on petroleum exploration and development, and the commercialization of three oilfields in one project (Elang-Kakatua)—a substantial investment which neither the companies nor Australian politicians are keen to lose.

Friends of Timor or Indonesia? (back to top)

Subsequent to the CNRT statement in 1998, there was a private meeting in Jakarta's Cipinang Prison between jailed Timorese leader Xanana Gusmao and Peter Cockroft, the Jakarta-based representative of Australia's BHP Petroleum, which has extensive interests in the Timor Gap. Gusmao reportedly told Cockroft that a Timorese government would protect the rights granted to BHP and other companies under the controversial 1989 Timor Gap Treaty between Indonesia and Australia.

On August 7, Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer expressed oppositionn to Gusmao's release and denounced the Timorese leadership's call for a referendum on self-determination, declaring that it would lead to bloodshed. But when reports of the BHP-Gusmao talks emerged, the Australian government changed its policy and called for the first time for Gusmao's freedom. "We would favor the release of Xanana Gusmao in the context of a process of reconciliation and settlement in East Timor." Downer announced on August 19. "Australia recognizes that Xanana Gusmao has a central role in the resolution of the East Timor issue."

Gusmao was reported to have assured Cockroft that, "BHP and other mining companies should not worry about the policies of the Timorese resistance". Xanana was also reported to have said: "We encourage them to stay on, looking to help the Timorese with the proceeds from the oil until a resolution is reached."

The Indonesian government reacted angrily to the Cockroft meeting and was moving to have him deported, but he was allowed to leave on his own after the Australian government intervened. He returned to Melbourne and little has been heard of him since. BHP also subsequently offloaded much of its interests in the Timor ZOC area, and earlier said it was definitely against the Phillips option of building a refinery in Timor. Did BHP put all its eggs in the Indonesian basket, a basket the Indonesians have now dropped? (Phillips has now purchased BHP's share in the huge Bayu-Undan field.)

Richard Woolcott, former ambassador to Indonesia and later secretary to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, in an article in The Australian Financial Review, said that both the current Howard government and the Labor opposition had seen a need to change their policies on East Timor to meet what he described as an "evolving situation in Indonesia". He noted that, "The changes could lead to substantial financial implications for the (Australian) government if the Timor Gap Treaty, were to unravel." As the major companies are exploring for oil and gas under the umbrella of the treaty, if Australian recognition of de jure Indonesian sovereignty over East Timor were abandoned, the treaty could be nullified, resulting in substantial financial claims.

Woolcott emphasized that "The principle of self-determination is not a sacred cow." Pointing out that the Timor issue provides a graphic picture of the way Western governments use lofty appeals to this principle to suit their commercial and strategic interests.

East Timorese leaders are, however, undoubtedly aware that any attempt to renegotiate the treaty could result in the deferring of economic benefits that would flow from the hydrocarbons in the very near future, putting East Timor in the position of needing aid from Australia, while trying to squeeze more from the Treaty—an invidious position. Another advantage of the income source is that it is offshore and not subject to the unsettling effects civil unrest are, and will have, on the country's meager income sources.

Timor Sea Players

The three key players in the Zone of Cooperation, with potential developments on their books, are Phillips, which is positioning itself as a major player in the area with its buyout of BHP Petroleum from the Bayu-Undan project, production from which is planned for 2003; Woodside and BHP Petroleum. Shell and Woodside are the major players in the Timor Sea area in general. Liquefied natural gas or LNG is a primary objective for the bigger fields.

The Future of ZOC hydrocarbons? (back to top)

Judging from the 'scorched earth' policy the Indonesian military has put into effect when 'voted out' of East Timor, it would be wishful in the extreme to say that the Indonesians will now gracefully give back to East Timor its oil fields, only the coming months will tell.