Low Cost, Sweet Crude, Abundant Gas, Nearby Markets Put Saharan Africa in the Reckoning

by Moses Aremu, Lagos

It is easy to assume that new oil in Africa comes only from the coastal basins of West Africa, but Libya, in the northeast, still has Africa's largest oil reserves. And between the "Great Jamahiriyah" and Algeria, there are some 36.7 billion bbl, far exceeding the reserves of both Angola and Nigeria.

It is easy to assume that new oil in Africa comes only from the coastal basins of West Africa, but Libya, in the northeast, still has Africa's largest oil reserves. And between the "Great Jamahiriyah" and Algeria, there are some 36.7 billion bbl, far exceeding the reserves of both Angola and Nigeria.

Even with Libya emerging from isolation and Algeria at war, North Africa led the world in 1998 (the last year for which figures are readily available in terms of new field wildcats(NFWs). There was a 12% increase in wildcats in North Africa, compared with a 2% drop in Middle East and 24% drop in North America. North African NFWs increased significantly in Algeria and Tunisia while decreasing marginally in Libya and Egypt in 1998. Algeria added 30 million boe per NFW after drilling 30, and Egypt added roughly 10 boe per NFW after drilling 50.

The level of activity—seismic, drilling, and production—anywhere, is the point at which three things converge: government incentives, a country's prospectivity, and the commitment of the oil operators. The North African countries have been generally bullish on incentives in the last two years. Operators have responded as much as they can, in the light of competition for funds elsewhere. And prospectivity, especially in Algeria, is relatively good.

Algeria(Back to Top)

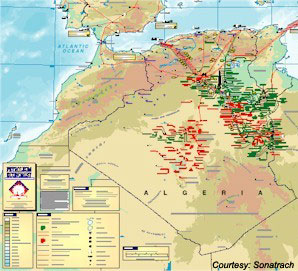

With Libya only now emerging from isolation, Algeria has been the focus of oil and gas activities in North Africa. With the largest store of gas in Africa (124 Tcf), it elbows Nigeria's 110 Tcf to second place; and its nearness to Europe guarantees a market. Algeria's 9.2 billion bbl reserves rank third after Libya's 29.5 billion bbl and Nigeria's 22.5 billion bbl.

Recent exploration successes have emphasized Algeria's prospectivity and confirmed its reputation as Europe's trustworthy gas supplier in Africa. Last month, BP Amoco and Sonatrach announced they were going ahead to develop a US$2.5 billion complex of gas fields—the In Sallah fields—in the Sahara. They will supply 9 billion m3 of gas to southern Europe. BP Amoco is also working on the In Amenas gas and condensate project, based on four fields in eastern Algeria for which Amoco signed a PSC in 1998. In Amenas will produce 700 million cf/d gas and 45,000 b/d condensate and LPG.

Recent exploration successes have emphasized Algeria's prospectivity and confirmed its reputation as Europe's trustworthy gas supplier in Africa. Last month, BP Amoco and Sonatrach announced they were going ahead to develop a US$2.5 billion complex of gas fields—the In Sallah fields—in the Sahara. They will supply 9 billion m3 of gas to southern Europe. BP Amoco is also working on the In Amenas gas and condensate project, based on four fields in eastern Algeria for which Amoco signed a PSC in 1998. In Amenas will produce 700 million cf/d gas and 45,000 b/d condensate and LPG.

But some of the most exciting stories in Algeria have been in regard to oil. Last September, after Elf's agreement to acquire a 40% stake in redevelopment of Arco's Rhourde El Baguel Field, the Anadarko-Sonatrach consortium awarded the next phase in the production of the Hassi Berkine Field. Since discovery in 1992, it has emerged as a huge world-class field. When it went on stream in October 1998, estimated recoverable reserves were 4 billion bbl. In September, operator Anadarko and Sonatrach, the Algerian state company, awarded a US$331 million EPC contract to Brown & Root Condor for stage two of the Hassi Berkine Nord -Sud (HBNS) production facility. The project includes a 75,000 b/d gas and oil separation train, gas injection, flowlines, wellheads, trunklines, and field-gathering stations. At completion in October 2001, it will increase capacity from 65,000 b/d to 285,000 b/d.

Sonatrach is keen on developing Ourhood, another huge oilfield, which straddles three blocks operated by Anadarko, Cepsa, and Burlington Resources. Sonatrach chairman Abdelmajid Attar, says US$1.2 billion worth of contracts may be signed this year for the development. Its share is part of the $21 billion five-year program to double oil capacity and increase natural gas output by 2004 using PSCs. The program envisages $16.4 billion for field development.

Meanwhile, Sonatrach discovered oil and gas on the Benkahla East structure in Oued Mya Basin, about 60 km west of Hassi Messaoud Field. Benkhala East-1 (Block 438) tested 3,650 b/d of 42.8° API and 3.77 million cf/d gas.

Meanwhile, Sonatrach discovered oil and gas on the Benkahla East structure in Oued Mya Basin, about 60 km west of Hassi Messaoud Field. Benkhala East-1 (Block 438) tested 3,650 b/d of 42.8° API and 3.77 million cf/d gas.

In 1999, Sonatrach negotiations for 11 exploration blocks began, and once more is luring international oil companies to unexplored areas. Majors responded by asking Sonatrach to sweeten terms and offer larger and potentially more lucrative acreage so they could justify venturing into remote desert areas with little or no infrastructure.

Companies want the existing PS model replaced with JVs that can offer longer term benefits and deliver cost reduction since both equipment and personnel can be shared with Sonatrach.

Algeria's investor-friendly, relatively new government of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika is keen on expanding the investment portfolio. The new Energy and Mines Minister Chakib Khelil, a former World Bank official, is expected to work on transforming the oil and gas industry, including reorganization of Sonatrach and the opening of non-core subsidiaries to private investors—but the state is expected to remain the majority shareholder.

Libya(Back to Top)

Libya's re-entry to the oil patch has come with more of a bang than a whimper. With oil prices higher than they have been in five years, the European energy industry has embraced the country with enthusiasm. Lundin Oil, Italy's ENI, and UK's Lasmo never withdrew during the sanction period. Libya's appeal to investors anywhere, anytime derives from three key things:

For European companies especially, there is supply security. Libya's 60 Tcf of gas, even though just about half of Nigeria's reserves, could provide extra gas to southern Europe for 20 years—which is why ENI has committed to a $3.8 billion project to export gas from the Wafa Field to Sicily and the mainland. The project is sure to go ahead now that sanctions have been lifted.

Sweden's Ludin Oil , in Libya since 1989, had invested $43 million through 1998 in development costs. Its budget this year is $11 million. Repsol and Lasmo are also carrying out major projects.

The major drawback to investing in Libya during sanctions was an embargo on certain equipment—the most painful of these was oil recovery technology, thus major oil fields suffered production dives, volumes from new fields have not compensated for the decline, and there is real danger that long-term production will slip below 1 million b/d. Other problems include a poor infrastructure.

The major drawback to investing in Libya during sanctions was an embargo on certain equipment—the most painful of these was oil recovery technology, thus major oil fields suffered production dives, volumes from new fields have not compensated for the decline, and there is real danger that long-term production will slip below 1 million b/d. Other problems include a poor infrastructure.

Although a new hydrocarbons law has been drafted since the lifting of sanctions, aiming to improve terms of upstream investment, Libya still lacks a proper commercial legal system, and its laws remain open to the vagaries of decree. Nevertheless, everybody other than the United States wants to have a look. Three months before the sanctions were lifted, Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) has an agreement with its Libyan counterpart to explore and drill. It will work in two of the 12 fields that Tripoli opened for exploration in 1995.

Energy Africa is examining open acreage opportunities, but plans are on hold while the Libyans review fiscal terms. And South African state oil company Soekor has been talking to the Libyan National Oil Company about investing in producing fields.

Now with the embargo on US companies still in force, Libya has called for bids on 80 new leases both onshore and offshore, mainly from European companies. In the meantime, a consortium of Repsol, OMV, TotalFina, and Saga has been awarded a license for the Murzuk Basin Block M-4, increasing their acreage by 12,300 sq km. The group holds a PSC in Blocks NC 186 and NC 187.

The USA is not likely to allow American firms to do business in Libya at least until the Lockerbie trial concludes, although four US companies, Occidental, Marathon, Conoco, and Amerada Hess, have visited to check on assets they abandoned in 1986.

Egypt(Back to Top)

Egypt's oil reserves are smaller than those of Libya and Algeria, with new finds more around 5-10 million bbl oil, but it is enjoying a surge of activities in its gas sector, though reserves are smaller than Algeria's and Algeria has already cornered the southern European gas market.

Egypt has a lot going for it: 1999 economic growth rates of 5.45%, up from 1998's 5%, respectable for an African country of 66 million, though 500,000 enter the job market yearly and unemployment remains at 18%.

Since 1990, the country's liberalization has achieved a substantial increase in foreign investment. Even with lackluster privatization efforts, other areas have encouraged economic growth. Reduction in state subsidies has brought down the budget deficit to 1% of the GDP. Liberalization in prices has occurred in all sectors of the economy, except, ironically, in gas pricing.

The buzz of activity in Egypt is around the deep offshore Nile Delta. In early 1999, BP Amoco with Elf and Shell this year took on large new deepwater tracts that are likely to find large reserves of gas rather than oil. Fortunately, the Mediterranean is one of the world's important gas markets; whatever cannot be consumed at home can be piped to Israel, Turkey, Syria, or Lebanon.

BG will spend more than $1 billion over the next three years in the project phase following a series of gas discoveries in the Nile Delta. First gas from the Rosetta Field, discovered in April 1997, will be produced in June by a JV of BG, Shell, Edison, and Egyptian General Petroleum Corp. The jacket already installed, the offshore pipeline laid, and construction of the topsides are in the final stages at the Petro-jet yard near Alexandria. The field will produce 275 million cf/d gas to be sold into the Egyptian gas grid under a long-term supply contract with EGPC. Four production wells have been drilled and will be completed after the topsides are installed, while another one or two wells will be drilled to reach the contracted level.

A consortium of BG, Edison, and EGPC will develop the Scarab/Saffron Field. It will be Egypt's first using deepwater subsea technology in depths of 700 meters. An initial set of eight wells controlled from shore will produce 530 million cf/d starting in early 2003. Apart from Rosetta and Scarab/Saffron, which hold some 6 tcf of gas, BG has another 4 tcf of gas or more reserves discovered on its West Delta Deep concession through the P12/P13 find and, most notably, the large Simian Field found earlier this year.

Oil fields in Egypt's Gulf of Suez are mature and in decline, and the Western Desert has not appeared extremely promising from the wells that have been drilled so far—nevertheless, analysts say it is not well explored.

The country's liberalization program has caused a vast increase in foreign companies seeking investment opportunities, with EGPC spearheading the appeal.

254 agreements have been signed in 25 years between 1973 and 1998. Of these, 191 or 75% were with foreign companies. Transnational companies have invested around $24 billion and increased Egypt's oil reserves from 313 million tons of oil equivalent in 1973 to 1.187 billion toe in 1998. Gas reserves stand at around 36 tcf. EGPC has also encouraged investment in more remote areas, including Qarun, south of Giza, Fayyoum, and Beni Suef, as well as in the Qattarav Depression.

Today, 49 companies from 19 countries are operating in Egypt and many are involved in the big projects, with investment in petroleum projects totaling more than $2 billion in 1997-1998 alone. While the Egyptians will not privatize EGPC and its subsidiaries, they are offering a 35% stake in the newly formed Misr Petroleum Processing Company—a move considered far-reaching to widening the ownership of the state sector, while, at the same time, maintaining sufficient control in a strategic part of the economy.

Egypt's improved economic statistics, even in the aftermath of the shocks of the last 24 months, should assure investors who participated in last October's licensing round for 15 exploration blocks, covering a total area of 171,374 sq km, earmarked for oil and gas PSCs with international companies. The prospectivity overrides every other concern, but even if it is only gas that is available, investors appear assured that this is one of the more stable investment venues in Africa.