The Dash for African Gas

Contents

Mozambique

Namibia

Tanzania/Kenya

Alba

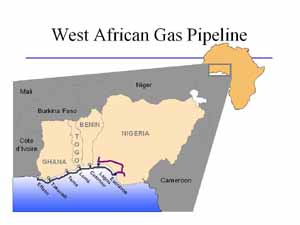

West African Gas Pipeline

When protesters attacked Nigeria's liquefied natural gas plant in Bonny in September, they damaged six of the nine wells feeding the process and forced a delay in the first shipment. Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG) Ltd, issued a force majeure to buyers of its first export cargo, and observers speculated that this could threaten failure of sales/delivery contracts signed with companies in Italy, Spain, Turkey, France, and Portugal. Newly elected President Olusegun Obasanjo intervened, however, and calmed the protesters, who were demanding compensation for exploitation of resources in their backyards.

Thus saved, the launch of the US$3.8 billion LNG project has boosted the entry of sub-saharan Africa into the world gas market. It is not Nigeria's first commercial gas export project, however. For the past two years, Chevron Nigeria has been exporting liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) from associated natural gas in its western oil fields, and Mobil has been monetizing the gas reserves in its huge Oso oil/condensate field. Together, the two companies produce an average of 45,000 barrels a day (oil equivalent).

Elsewhere in West Africa, Cote d'Ivoire started operating the first commercial natural gas/power project in 1995. More than 100 million cf/d of natural gas is delivered to the Vridi Gas Terminal from the Panthere Field to fuel an electricity plant that supplies all of the capital Abidjan. In Equatorial Guinea, production of LPG began in 1997, using wet gas from Alba Field.

Bonny LNG Plant. Courtesy Shell Nigeria.

But the entry of NLNG into the scheme of things raises the profile. Nigeria is ranked No.12 in the world in terms of oil reserves and sixth as an oil exporter. Its Niger Delta basin holds the 10th largest gas reserves on the planet. With 114 tcf, Nigeria has hardly tapped its gas resources, other than to flare those that come out of wellheads with the oil, to the dismay of environmentalists. The country has the highest ratio of reserve to production on the list of 19 countries with over 50 tcf of gas reserves each. No other African country, apart from Algeria, is in this elite club. But Algeria is well positioned; it depends, for its gas export, on the captive European market, across the Mediterranean.

Africa, as a rule, doesn't utilize energy on its own. Markets are nonexistent, and gas-rich African countries far from Europe have had to flare gas produced in association with oil and leave gas fields undeveloped.

Such was Nigeria's lot, but things have changed. The crisis in the Niger Delta has seen communities rise up to campaign against the environmental degradation caused by, among many things, gas flaring.

The Bonny plant, estimated to cost $3.8 billion, is enormous, virtually a city in itself. The project is owned by a consortium which includes the state oil company NNPC (49%), Shell (25.6%), Elf (15%), and Agip (10.4%), and is committed to supplying gas to European customers for the next 22.5 years. Although the NLNG project has been in place for 30 years, it is being realized just as a slew of gas projects are being developed all over Africa-some of the most active areas in Southern and East Africa.

The dismantling of apartheid opened the eyes of South Africa, an industrial country, to the gas resources next door in Mozambique. Whereas in East Africa, the exploitation of offshore gas will alleviate local dependence on diesel fuel and hydroelectricity for power generation and help boost local industries.

Mozambique

In Mozambique, the Temane gas field, discovered by Chevron (then Gulf) in the 50s, has now become of commercial value. In the southern province of Inhambue, it is twice as large as Pande, country's other major gas field, with estimated reserves of 27.7 million cf/d-enough gas to provide about 10% of South Africa's energy demand, according to analysis. The consortium involved in its production includes Sasol (47.62%), Arco (47.62%), Zarara Petroleum Resources (4.76%), and Mozambique state oil company ENH.

Until two years ago, the Pande gas field was the central issue for investors keen to establish a presence in Mozambique's hydrocarbon industry. It was to be tied to industrial development via a pipeline to Maputo, the capital, where it would help develop the Maputo Iron and Steel project. But all of that idea is being shelved now, as a result of the wide gulf between Enron and the Mozambican government. Enron would have coordinated the project with financing by such investors as South Africa's Industrial Development Corporation, the International Finance Corporation, Credit Suisse, First Boston, and DUFERCO, the largest privately owned steel trader in the world. Some $1.6 billion has already been spent on the field, 25% of which came from the IDC and another 25% from Enron.

Now that Pande has been rolled over, the sights are on the gas-rich coastal area from Beira to Vilanculos. Temane lies inland to the north of Vilanculos and Pande lies just a little further north, near Mambone. If proven, the Sofala Field and M10, two newly discovered gas pools, may be exploited to supply gas to Beira whereas Temane will be utilized exclusively for Sasol projects in Johannesburg and Pretoria. M10 lies close to the shore, southeast of Beira.

The most conservative estimates indicate that 812-1,766 million cf/d of gas can be extracted from the Temane Field for the next 50 years. The consortium has spent close to $60 million on the project, with seven wells drilled, and is spending $600 million to build a 925-km pipeline to link Temane with Sasol's South African operations.

Namibia

From a utilitarian point of view, Namibia's Kudu gas field is less problematic than Mozambique's Pande. Discovered in 1973 by Chevron, Kudu holds at least 2 tcf of gas. It is located in Block 2814A, 130 km offshore southwest Namibia, and is licensed to Shell and Energy Africa. Other than the South African Eskom power generation project, there is no other market for Kudu gas, which will be piped 550 km at a rate of 7.7 million cm/d. Shell has a partnership with National Power of the UK and Eskom of South Africa to carry through this project. The plant is scheduled to be the fifth largest gas-powered facility in Africa and is proposed to come on stream in 2001.

Shell and partners will finance the estimated $350 million cost of bringing Kudu into production, but Shell, Namibia Power Corporation (Nampower) and Eskom will jointly build the $500 million 750 MW power station.

Another estimated 7 tcf of gas reserves are believed to lie within the Kudu license area which could fuel future development of South Africa's Western Cape. Shell expects to conclude a major contract with Eskom to permit a second phase development.

Tanzania/Kenya

The stakes are lower in Eastern Africa, with more modest economies than Nigeria and Southern Africa. Less than 10% of Tanzanians have access to electricity, and the few industries are inadequately supplied. Now the country is keen on improving this situation, and is looking to the Songo Songo gas field, on Songo Songo Island and the Mnazi Bay gas field to feed a pipeline network for industrial consumption.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was signed in 1993 by a consortium composing of Ocelot, TransCanada Pipelines, the Tanzanian government, and the World Bank. The project will be expanded when Kenyan state electrical company gets involved.

The large, high pressure gas pool in the Mnazi Bay, near the southern border with Mozambique, is expected to fuel a project by Tornado Resources and Caterpillar Power Ventures. The two companies are working to bring gas to a 15MW power generation plant in Mtwara powered by diesel. The Tanzanian government wants to make Mtwara, a deep natural harbor, into a regional trade hub. The proposed gas-fired reciprocating engine at Mtwara would provide power to the neighboring towns of Lindi and Masasi, through an expansion of the regional transmission infrastructure.

Tornado Resources estimates the bill for the Mnazi-Mtwara project at $27 million. It involves re-entry into Mnazi Bay-1 well, in 18 ft water depth at high tide, running a dual completion on two of the seven gas zones, and constructing a 24 km pipeline (7.7 km of which will be marine) from Mnazi Bay to Mtwara.

Alba

In Equatorial Guinea, the Alba Field will provide fuel for Atlantic Methanol Production Co. (AMPCO)'s new methanol plant, under construction on Bioko Island. The plant's output will be used to make chemicals, solvents, fuel additives, and building materials. Two US companies, Samedan Oil and CMS Energy, each hold 45% share in the plant, and Equatorial Guinea holds 10%. It is expected to produce 19,000 bbl/d of methanol. The $300-million plant, constructed by Raytheon, is expected to be operational by the end of 2000. Gas produced from the Alba Field has been flared since condensate production began in 1991.

CMS Nomeco and its Alba Field partners plan to conduct tests on an additional discovery made in Block E, the same exploration block that contains the Alba Field. The find, Luba East, located four miles north, produced 18 million cf/d of natural gas from its initial test. The well also produced 2,100 bbl/d of condensate. If deemed commercially viable, production may begin right away.

A new gas-fired 4-6 megawatt (MW) capacity electricity plant is also under construction in the CMS Nomeco complex on Bioko. This build-operate-transfer (BOT) project will radically alter a national energy balance in which only 5 (MW) of electricity generating capacity has been available up to now. Gas supplies for the new plant will come from existing sources (Alba Field), as well as future associated and non-associated gas finds offshore Bioko.

The much touted 524-mile West Africa Gas Pipeline finally looks like a real possibility, with the governments of four West African countries finally signing a memorandum of understanding. The project is meant to deliver Nigerian natural gas to Benin, Togo, and Ghana. The signing of the MOU was followed by a joint venture agreement (JVA) among a consortium of six companies from the four participating countries. The companies include Chevron Nigeria Limited, Nigerian Gas Company Limited, Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited, Ghana National Petroleum Corporation, Society Beninoise De Gaz and SoToGaz of Togo. The pipeline will take 24 months to build and startup at 100-150 billion cf/d capacity rising to 600 billion cf/d over 20 years. It will run along the coast west of Nigeria from Escravos to electrical power plants and manufacturing sites in Benin, Togo, and Ghana.

For Chevron, the initiator of the project, the WAGP is a natural follow up to the Escravos Gas Project, which is in place to gather and process 285 million cf/d. For observers, it is the most compelling argument for an African gas grid. The thesis is that the three growth factors that have moved the world's large markets (Europe and America) forward in the last 20 years are coming together in Africa today. They are; access to large reserves; the need for increased capacity in power generation, and the need to add value to primary energy resources.

A Dames and Moore study commissioned by Chevron suggests that between 10,000 and 20,000 primary sector jobs will be created as the new power supply stimulates the growth of new industry. The study also identifies $1.8 billion in total capital investment for the region as a result of the pipeline project. This includes $400 million for the pipeline, another $600 million for the power plants and $800 million in new industry.

Optimists believe, in fact, the success of the WAGP will show the path to gas developments in other regions in Africa; Kudu, Temane, Mtwara, and others.